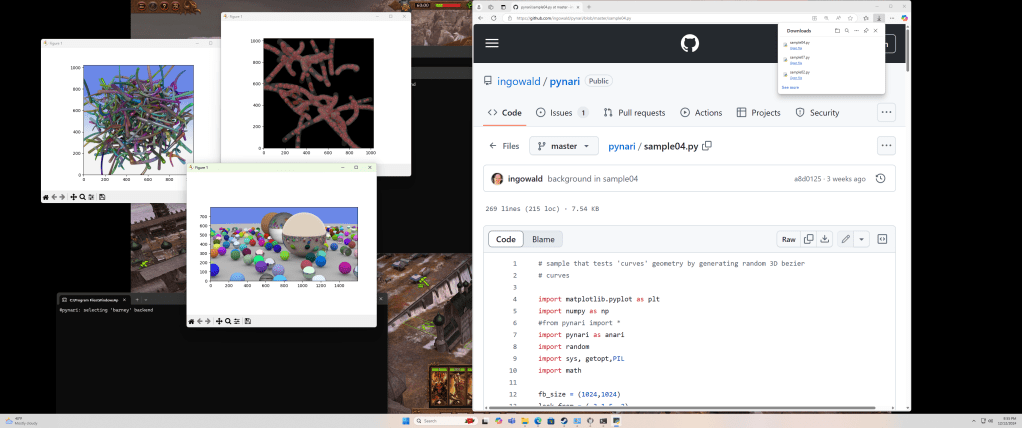

This article is about a capability – and in particular, about the “how do you actually use that” – that i recently added to Barney, namely, to do data-parallel multi-GPU rendering through Barney’s ANARI interface layer. This is not a comprehensive discussion about barney, or data-parallel rendering in Barney, but enough people asked about this that I think it’s easier to explain this once in a blog, and share it this way, instead of trying to explain over and over again in email and slack (of course, an actual paper would be even better, but that’d take much longer, and I don’t want anybody to have to wait for that … so here we go).

The Problem

‘K, for those that already know what the problem is: just skip this section, and jump to “ANARI Device Tethering”. For those that don’t, let’s first explain the problem: The core of the problem is that “data parallel rendering” refers to rendering where the model is actually split across multiple different GPUs and/or nodes, and since that’s a totally different beast than “regular” rendering on a single GPU (or even replicated rendering where each GPU has a full copy of the same model) this can create all kind of issues.

More specifically, Barney itself (ie, the renderer I recently worked a lot on) can natively do data-parallel just fine, and it can do that in both MPI and non-MPI multi-GPU ways – but the Khronos ANARI 3D Cross-Platform Rendering API layer that most users would arguably want to use Barney through has no actual notion of data parallelism, so it can’t easily express this. Barney itself has an explicit notion of both multiple GPUs as well as multiple “data ranks” within a single barney context, and is just fine with the app loading different data onto different GPUs, and then asking the (single) context to render an image across all those different GPUs’ different data. That’s a capability built deep within barney from the very beginning, and it’ll do that just fine. This article is not going to discuss how that is done, or what it all can or cannot do – let’s just assume it can. Barney can actually do this data parallel multi-GPU thingy both over MPI (each MPI rank can have its own data) as well as for single process that doesn’t even know about MPI (and instead specifies multiple GPUs and data ranks with that same context)… and it can even mix the two in all sorts of ways (so yes, you can have N ranks with G GPUs each, having D <= N*G different types of data, affinities, etcpp).

How it does that does not matter for this post – but what does matter is that users would likely want to use Barney not through it’s “native” API (which explicitly supports all that stuff), but would instead want to use it through the Khronos ANARI 3D Cross-Platform Rendering API (which Barney also supports)… but the ANARI API doesn’t have any native concept of “data parallel”, yet … so that’s a problem. For the most common way of using data-parallel rendering in Sci-Vis (which is over MPI, with different data per rank) we already proposed and described a ANARI “Extension” that would allow using that in Barney (more details on this in this 2024 LDAV paper), but this one has the catch that the user has to use MPI to use that … and not everybody is comfortable with that (a notion I can fully understand, actually).

As such, the problem we faced was that Barney already does have a concept of data parallel multi-GPU within a single process, but ANARI does not. To dig a little deeper, the problem is that if you do want to do data parallel single process rendering you have to deal with the fact that some “entities” in the rendering process are intrinsically “per process” (ie, you have one model, and one frame that you’re rendering, etc), but others are intrinsically “per device” (one geometry might live only on one device, others only on another)… but in ANARI there is only one device to create all of these entities, and no way to say “but this goes here, and that goes there).

Now for the MPI-based data-parallel ANARI extension mentioned above we allow the user to express this on a per-rank way – different ranks implicitly load different data, but then do some calls collectively – but this doesn’t easily work within a single process. The “different ranks have different data” you could still express as different devices (actually, that’s what we do as well), but the entire “collective” thing becomes a bit more tricky, and does not actually map all that well.

ANARI “Device Tethering”

So, the way we decided to realize that same functionality in (B)ANARI is through what we call “tethering” of devices: Basically, there will be N different devices (one per GPU), but these are all “tethered” to a single “leader” that plays a special role. Basically, the lead device is the one to talk to for any sort of “per process” operation (like creating a frame, rendering a frame, mapping a rendered frame buffer, etc), while all the other devices exist merely to describe how to create data on different GPUs – and the “tethering” expresses that – and how – these actually belong together. Ie, because the other devices are all explicitly tethered to that lead device, that lead device will know that there are other GPUs, that they each have different data, but that it is responsible for doing all the work.

So, how does that work in practice? Basically, that answer splits into two separate categories: How to initialize the whole thing (such that there are N devices that know they’re tethered together), and how to then use that during rendering.

Initial (Tethered) Device Setup

Basically, almost all the secret sauce lies in the initial setup and device creation, where we have to create the N different devices, tell them which is to run on which GPU, and tell them who’s the leader, and how they’re tethered together.

To do this, the first step is to prepare our app for having multiple different devices (one per GPU), so instead of having a single ANARIDevice you’d probably have something like this:

int numGPUs = ...;

std::vector<ANARIDevice> dev(numGPUs);

Now, the first step is to create the lead device. This lead device is like any other device (ie, we can also load data onto it), so we’ll just store it as dev[0] – we’ll just know later on that it has a special role to play. Creating that lead device would work just like any other device

// load barney - note this loads the non-MPI barney device!

ANARILibrary barney = anariLoadLibrary("barney", ...);

dev[0] = anariNewDevice(barney,...);

… except that we’ll also tell it – through some specially named parameters – that it’ll eventually be one of many. To do this we set the variables tetherCount and tetherIndex. Through the first we’ll tell this device how many others there are, through the second, we’ll tell it that it’s the first (and thus, implicitly the lead) device:

anari::setParameter(dev[0],dev[0],"tetherIndex",(int)0);

anari::setParameter(dev[0],dev[0],"tetherCount",numGPUs);

anari::setParameter(dev[0],dev[0],"dataGroupID",(int)0);

anari::setParameter(dev[0],dev[0],"cudaDevice", (int)0);

Note how each of these calls has the dev[0] parameter twice – this is not a typo, but actually correct: the first one is handle to the device that is setting the variable, the second one the object that this variable is being set on… it just so happens that this device has to set this variable on itself, but that is correct. Note that through the cudaDevice variable we also explicitly tell that device to run on GPU 0.

Also worth explaining is the "dataGroupID" parameter: In barney, data parallel rendering is realized by giving each device (actually, each of what Barney calls a “data slot”) a numerical index that describes what part of the entirety of the data it will have. Not which exact geometries or objects – those are going to come later, through anari entity creation calls – but what logical part of a hypothetical whole: If you create two devices that each have their dataGroupID set to 0 (or don’t set this variable at all, because 0 is the default), barney will interpret that as you guaranteeing that these devices will have the same data loaded onto them eventually – so it can use those devices in a data parallel manner. But if you tell the first device that is has data group ID 0, and the second one that it has data group ID 1, then barney knows that there’s two different kinds of data, that that these two devices need to work together to produce the right output. You can also do things like setting GPU0 and GPU1 both to ‘0’, and then setting GPU2 and GPU3 to ‘1’, in which case Barney will have GPU0 and GPU2 working data-parallel on some pixels, and GPU1 and GPU3 working together on others – but let’s not go into that in detail – bottom line is that if you have N different devices, and set each device’s data group to a different numerical ID, barney will realize that you want these devices to be run in data parallel mode (and yes, please use numerical IDs 0, 1, 2, etc; not 13, 47, 3, etc… I assume that’s what any sane person would use, so didn’t even bother to implement the latter).

Now at this point, it is time for this device to be committed, so it’ll actually know about these variables:

anari::commitParameters(dev[0],dev[0]);

At this point, our lead device is created, and it can initialize itself. In particular, it will also know that there will eventually be more more devices that will try to tether themselves to it. At this point you cannot actually use that device yet, because it’ll wait for those other devices to be created before they can then all together finish their setup (just to say this again because it is important: This device is not yet ready to be used for rendering – we told it that there’s some other devices coming up, and we cannot use this device for actual rendering calls until these have been created, too!). So, let’s create the other devices, and tether them to that lead device:

for (int i=1; i<numGPUs; i++) {

// this is the same as for dev0

anari::setParameter(dev[i],dev[i],"tetherIndex",(int)i);

anari::setParameter(dev[i],dev[i],"tetherCount",numGPUs);

anari::setParameter(dev[i],dev[i],"dataGroupID",(int)i);

anari::setParameter(dev[i],dev[i],"cudaDevice", (int)i);

// this is to tell those devices who to tether to:

anari::setParameter(dev[i],dev[i],"tetherDevice",dev[0]);

anari::commitParameters(dev[i],dev[i]);

}

This initialization code is almost identical to the one for GPU 0 (in fact, it can be run in the same loop), except that the "tetherDevice" variable cannot be set until dev[0] has been created and committed (and it may, in fact, not be set on dev[0], because this variable being null is what tells that device that it’s the lead device). Luckily ANARI already has a notion of setting object handles as parameters, and because an ANARIDevice is also implicitly a ANARIObject, both the setting of parameters on devices, as well as passing a device as a tetherDevice parameter all worked out of the box. Also note again how each GPU gets a different cudaDevice and a different dataGroupID. This is exactly how we tell each device what GPU to run on, and that they all have different data).

After this initialization step, we’ll have numGPUs different devices, each on a different GPU (cudaDevice), each expecting different data (dataGroupID), all knowing that they’re tethered together, and all knowing that dev[0] is the lead device. Also, all devices have been committed now, are now all fully initialized, and can now be used for other ANARI calls.

ANARI Rendering with Tethered Devices

With these properly tethered devices now created, we can do rendering almost identical to how it as done before. Basically, I assume that your existing (single GPU) ANARI workflow for a non-data parallel app looks something like this:

// load app-specific model

MyModel model = loadModel(....);

ANARIDevice device = createMyAnariDevice();

// issue anariNewVolume, anariNewGeometry, etc calls

ANARIWorld world = createAnariWorld(device,model);

// create a frame to be rendered

ANARIFrame frame = anariNewFrame(...);

// assign instances to this frame

anariSetParameter(frame,"world",world);

// render an actual frame

anariRender(frame);

// and read back the frame

float4 *pixels = anariMap(frame, "color", ...);

I’ve obviously taken some liberties with ANARI here – this isn’t literal code – but if you already have a single-device ANARI implementation I’m fairly sure you’ll recognize what I mean.

Four our data parallel device, this will be fairly similar in concept, with just a few differences. Most obviously, you won’t have one model in your app, but will have one per GPU. Whether you load a pre-partitioned model, or partition a model on the fly, or extract it on-the-fly from some other data already on the GPU doesn’t matter, but conceptually you’ll have something like this:

// create partitioned model - one 'model' per GPU

std::vector<MyModel> modelPerGPU(numGPUs);

for (int i=0..numGPUs)

modelPerGPU[i] = createModelForGPU(i);

We can now create our tethered devices, using the code we described above:

std::vector<ANARIDevice> dev = createTetheredDevices(numGPUs);

Remember this looks like just N different devices, but we know that dev[0] is special, and that the others are tethered, so they belong together.

Now with that we can also render our geometry as before, but of course, we’ll end up with a different ANARIWorld object for each GPU. So again we simply have the same we had before, just once per device:

std::vector<ANARIWorld> worldPerGPU(numGPUs);

for (int i=0..numGPUs)

worldPerGPU[i] = createAnariWorld(dev[i],modelPerGPU[i])

Note how each createAnariWorld() call uses a different device – that means that you can use the exact same createAnariWorld() function you had before – by simply giving it a different device (which knows that it’s on a different GPU) all the ANARI geometry/volume creation calls you make within this createAnariWorld() will automatically get routed to that device – and thus, (only) this device’s GPU . The objects created on that specific GPU’s device will only appear on that device, they won’t even be valid or other devices, and no other object that isn’t on any other device should ever even know about it.

Similarly, we now create one frame per device. In theory we’d only ever want a single frame (we’re not rendering N different image, right!?), but one of the “quirks” of ANARI is that the “world” to rendered is specified as a variable on the frame object. And since we have N different world objects we also have to have N different frame objects to set this variable on. So, once again we have something “per device”:

std::vector<ANARIFrame> frame(numGPUs);

for (int i=0..numGPUs)

frame[i] = anariNewFrame(dev[i],...);

We can now also set each devices’ frame’s "world" to the set of instances we created on that device:

for (int i=0..numGPUs)

anariSetParameter(dev[i],frame[i],"world",worldPerGPU[i]);

Note again how these have to match: a world created on device i have to be set on the frame created on device i, because otherwise the handles wouldn’t even be valid.

Now at this point, it’s important to mention one important thing: At this point, it is clear to us that these frame “belong together” in that they each store one GPUs’ worth of data that we know belong to a single logical model … but there has to be some means for barney to recognize that, too. The easiest would be if we could pass all N frames to the anariRender() call, but that call takes only a single frame parameter, so we need another way to express this.

One way to do that would be to explicitly tether those frames as we did for devices, and that would surely work … but we found this to be too cumbersome. Instead, what we do in Barney is to i assumes that it is the order in which frames are created on the different devices that expresses this tethering relationship: If each one of 8 (tethered) devices creates exactly one ANARIFrame each, then obviously it’s these 8 ANARIFrame handles that logically belong together (or better: whose “world” variables belong together!). Similarly, if each one of those two devices creates two frame objects, the first one of each belong together, and the second one of each belong together, etc. As such, each (logical) frame always has to be created once on each device (you’ll probably only ever need one frame per device – I do – but still…).

Barney will also assume that frames that logically belong together are always resized and formatted in a consistent manner across all device, so a resize would resize each such frame handle:

// properly set size and format of "the" frame (on each dev!):

for (int i=0..numGPUs) {

anariSetParameter(dev[i],frame[i],"size",...);

anariSetParameter(dev[i],frame[i],"channel.color",...);

anariCommitParameters(dev[i],frame[i]);

}

Now that all “the” model has been created and “its” instances have been set, we can proceed to rendering and mapping of the rendered pixels – but because barney will know that these different frame handles are actually all referring to the same logical frame and model, we can issue this call for only dev[0], and frame[0] … and barney will know what to do:

// this is only one PER PROCESS, NOT per device!

anariRender(dev[0],frame[0]);

At this point, barney will start rendering, using, on device[i], the world stored on frame[i]. It’ll actually only fill the pixels on frame[0]; the other ones are only there to hold their respective GPU’s “world” variable. Once rendering is done we can map “the” frame as usual, using the lead device’s frame handle, as before:

float4 *pixels = (float4*)anariMap(dev[0],frame[0],...);

Unlike all other calls, renderFrame() and mapFrame() are only ever called on device 0 (the frame handles for other devices only exist to store their respective device’s “world”) and that is actually the point, because anariRenderFrame() can only take one device and one frame – which is why we had to do this entire tethering in the first place, because now that one device internally knows that it is only part of a bigger group.

Final Notes

This was a long blog – much longer than expected. In fact, this almost makes it sound like this was a super-complicated thing to do – but in practice, the exact opposite is true. I just wanted to make clear to explain how this all works in detail (becomes somebody will ask, and it’s easier to point to one detailed write-up), but what you’ll realize is that if you already have an existing ANARI renderer then implementing this is going to be trivially simple: In my own main model viewer (called Haystack) adding this (once it was implemented in barney) was a thing of a few minutes, and it only affected a few lines of code (out of thousands). In fact, I’m almost certain you’ll spend more time dealing with how to even load or partition data into multiple different, per-gpu models – but once you have that, and you have code that can render your geometries and volumes into “a” ANARI device … then you simply create the N different devices in the tethered way described above, and call your anari render function once for each device.

Anyway, that’s enough for today; barney doesn’t write itself, not does it get better by me writing blogs. Take care, and if you dare, have fun playing with this.